The Chessboard Fallacy

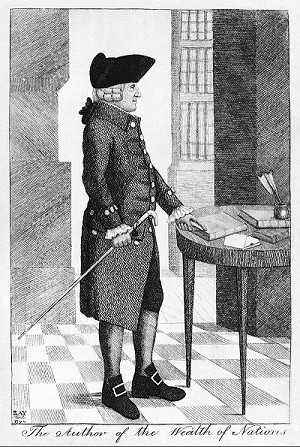

In How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life, Russ Roberts discusses Adam Smith’s idea of the Chessboard Fallacy. The idea comes from the following section of Adam Smiths’ The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Smith is discussing an approach to politics in which a leader has a system that they think will fix the world and plan to impose it upon their society. He calls such a leader “the man of system.”

He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board. He does not consider that the pieces upon the chess-board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it. If those two principles coincide and act in the same direction, the game of human society will go on easily and harmoniously, and is very likely to be happy and successful. If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder.

Roberts points to disastrous dictatorships as examples of this approach to politics — Pol Pot, Stalin, Mao. But the fallacy exists in a smaller scale as well and can apply to policies within more reasonable governments — one example Roberts uses is the war on drugs.

Yet the war on drugs has failed despite the desires of those kind, empathetic, earnest people and despite the harm that comes to drug users. The war on drugs has failed because too many chess pieces have their own movements; too many people like to use drugs. And too many people see those desires as a potential for profit, which it surely is. It’s very hard to stop that natural propensity to truck, barter, and exchange. Transactions will take place between people who want to use drugs and those eager to serve that desire because of the profit that follows. You can try to stop them, but it’s like squeezing a balloon over here — it tends to swell back out over there.

So how do we effectively change society? Roberts suggests it is through cultural change.

Despite the legality of smoking, per capita consumption of tobacco in the United States fell by 50 percent in the last half of the twentieth century. That’s a massive change. Sure, say the critics, but we could have and should have cut it to zero. But that’s a fantasy that ignores the chessboard and the natural movements of the pieces on it. Leaving it legal opened up the field for other ways to deter smoking. Some of those ways were legislative — restaurant smoking bans, for example, and taxation — but most of the change was cultural and emerged from the bottom up. Smoking is no longer cool or hip, as it was in the first half of the twentieth century. The cultural norm that smoking is a dirty and dangerous habit emerged with the accumulation of medical evidence and the individual reactions people had to that evidence.

So what logical conclusion does Roberts draw from this chain of thought? Perhaps that it is more important to focus on your own contribution to cultural change than it is to attempt to unilaterally enact your ideas upon others.

By reminding us of the perils of the man of system, Smith is reminding us to be wary of hubris. We think we can move those chess pieces where we want. We think we know what’s best for them. Smith is saying that even when we’re right, even if we think we know what’s best for others, sometimes it’s best to leave them alone, because our efforts won’t just fail or fall short of the idea. Sometimes they’ll do more harm than good. Sometimes it’s best to walk away from the board and set our sights on smaller, better fields of play than the chessboard of society.

Several related tangents I’ve been thinking about:

1) Intelligence is evenly distributed 2) Human beings have not become significantly more intelligent over time

These are very subtly different from the points of

1) Education is unequally distributed 2) Humans have become incredibly more knowledgeable over time

I don’t have a grand point, but, I think these distinctions are related to how we try to create change. When they are ignored, they miss some fundamental truth about how deeply all humans are the same while also being so insanely different. And when those differences and similarities are misunderstood or brushed over, you can fall into the trap of trying to move all the chess pieces where you think they should belong.

Member discussion